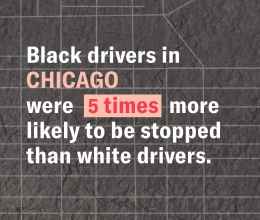

Chicago police officers stopped 200,000 more motorists in 2018, compared to the previous calendar year. The astronomical increase meant that CPD officers made more than 500 additional vehicle stops per day across the City. Minority motorists in Chicago were stopped more often than white drivers, comprising a remarkable 421,500 of the nearly 490,000 total traffic stops for 2018 – a number significantly higher than the percentage of motorists of color in Chicago. Black drivers were especially overrepresented with more than 300,000 traffic stops in 2018. This public information is available from the IDOT Traffic and Pedestrian Stop Study website.

“CPD has not explained publicly this astronomical increase of more than 200,000 vehicle stops in Chicago over one year” said Rachel Murphy, Staff Attorney at the ACLU of Illinois. “CPD must explain why it continues to stop more and more drivers each year.”

“Without CPD’s explanation, we can only infer that traffic stops simply became a substitute when problems with stop and frisk were made public. The reality remains simple – nearly everyone driving on the roads and streets has violated some minor traffic law, but drivers of color continue to be stopped at higher percentages than their estimated local driving population, and they are asked to consent to searches more frequently, with less contraband found, than white drivers.”

Traffic stops in Chicago have risen dramatically over the past few years. In 2015, CPD conducted 85,965 traffic stops. For 2016, the number increased to 187,133. 2017 grew even further, leading to 285,067 stops. And, for this year, that number exploded to just short of 489,000.

This data is part of information released earlier this year by the Illinois Department of Transportation. The data is collected under a law first adopted in 2003 under the leadership of then-State Senator Barack Obama. In late June, Illinois Governor JB Pritzker signed a measure into law that makes the collection and release of the data about traffic and pedestrian stops permanent. Without the new law, 2019 would have marked the last year that the data was collected and analyzed on a statewide basis.

Over the past fifteen years of reporting, the data has consistently revealed that Black and Latinx motorists in Illinois are more likely to be stopped by police and more likely to be asked for permission to search their car – even though police are more likely to find contraband in the cars of white motorists. Black and Latinx motorists in Illinois remain more likely to be stopped by police for traffic violations and more likely to be asked for consent to search their car.

A report by the ACLU in March 2015 showed that Chicago police were using stop and frisk at a rate higher than New York City. The ACLU report also showed that Black Chicagoans made up nearly 75% of pedestrian stops, even though Black people are only about 33% of the City’s population. After the ACLU report and an agreement between the organization and the City led to a marked decrease in pedestrian stops, CPD began to ramp up traffic stops.

Traffic stops still are a problem across the State of Illinois, showing a continuing pattern over recent years. For example, law enforcement reported conducting 2,470,322 traffic stops statewide in 2018. In 2018, minority drivers in Illinois were 1.65 times more likely to be stopped by police than would be expected based on the estimated minority driving population, an increase from 2017 when the same ratio was 1.49. Nearly one in five (19%) of the jurisdictions across the state had a ratio that was 2 or greater.

The 2018 data also shows that when the car of a white driver was searched based on the driver’s consent, police officers discovered contraband 34% of the time. On the other hand, when cars of Black and Latinx drivers were subjected to consent searches, police officers found contraband only 25% of the time.

“Every mayor, police chief, patrol officer, city council member and community group – in every city and town across Illinois – should take advantage of this valuable tool. They should look at the data for their community and discuss it, learn from it, and work together to make changes,” Murphy added.