Illinois General Assembly Joint Hearing With Senate Criminal Law Committee and Senate Special Committee On Public Safety

Subject Matter On: Police Training & Use of Force

September 1, 2020

My name is Karen Sheley and I’m the director of the Police Practices Project at the ACLU of Illinois. Chairman Sims, Chairman Slaughter, members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I represent clients who have been harmed by police violence and I thank you, on their behalf and on behalf of the ACLU of Illinois, for focusing on this urgent issue.

Americans today may appear divided on many issues, but Americans of all racial and ethnic backgrounds are united in calling for significant and systemic changes to policing. In a recent poll, nearly 80% of people think that police violence is a serious issue.

People from all walks of life have taken to the streets to demand change, only to be confronted by police wearing riot gear, driving armored trucks, and brandishing military rifles. In these situations and others, police officers exhibit a “warrior mentality,” handling common interactions with the public with overwhelming unnecessary force and the tactics and tools of an occupying army.

This is the moment to implement real – and overdue – changes to policing. The need for this change is reflected in countless stories and names. In Illinois, we are called to act by the deaths of Laquan McDonald and Jemel Roberson, and the lasting harm to Jaylan Butler and too many others to name. And in our neighboring states, names like George Floyd, Jacob Blake, and Breonna Taylor are etched into our collective memory, part of a tragic narrative that draws us to righteous anger.

I represent Jaylan Butler, the only Black member of the Eastern Illinois University men’s swim team. In early 2019, Jaylan was on a team bus in the Quad Cities area when the team stopped for a break.

Jaylan got off the bus to stretch his legs, when he was surrounded by officers with guns drawn. Calling on lessons from his father, Jaylan threw his cell phone down and dropped to his knees. Officers shoved him into the snow, and one pinned him to the ground by pressing a knee into his back. Another officer put a gun to his head and threatened to kill him with language I won’t use here. Only the school’s bus driver, a veteran, intervened – not another officer, even though Jaylan had done nothing wrong.

After the killing of George Floyd, Jaylan acknowledged he was fortunate to survive, but that the trauma has stayed with him, reignited by all of the many reports and videos of police killing Black people.

We need stricter and clearer restrictions on when and how officers use force because current federal and state law standards are not sufficient to prevent police violence and protect Black lives. Five years ago the General Assembly engaged in police reform. We are here again, but the moment now is even more critical.

We have an opportunity – and an obligation – to be bolder in our vision than we were then. That starts by accepting the difficult truth that – despite previous efforts by many people acting in good faith – the reforms enacted five years ago are not enough. We must make the commitment to change policing in Illinois. Otherwise, we will face more police violence, more protest, and a future where skin color continues to dictate whether you are killed or seriously injured by a police officer.

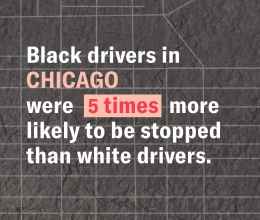

We need major changes to protect Black lives. We know that race is a key driver in police interactions. We see it in our communities and on the news, but also in the data collection about pedestrian and traffic stops that this body had the leadership to make permanent. Without meaningful restrictions on police use of force, every interaction with police – even for traffic stops and minor violations – creates the potential for a deadly interaction.

We must join the growing number of states across the country that are taking concrete steps to limit police use of force. As the General Assembly grapples with this issue, we propose some common-sense limits on use of force, and greater accountability for police who use it. Any police reform legislation must directly address police use of force in four ways:

FIRST: Illinois needs explicit limitations on use of force.

For example, force should be used only if absolutely necessary to protect against an imminent threat of bodily harm, all reasonable alternatives have been exhausted, and force can be used in a manner that minimizes injury to the person and bystanders. Deadly force should be prohibited unless absolutely necessary to prevent imminent death or serious bodily harm.

SECOND: Illinois should ban the tactics and tools that often result in unjustified force, including deadly force.

We must completely ban chokeholds and other methods used to asphyxiate individuals – like the extreme chest and back compression that killed George Floyd. And tear gas, sonic cannons, and rubber bullets must be prohibited. These have been used in response to people engaged in protest. That is wrong. We must also ban police departments from accepting military equipment, and decommission military equipment from police department arsenals.

THIRD: We must require consistent accountability from officers.

Officers must hold each other accountable by “safely interven[ing] by verbal and physical means” when they “observe another peace officer use any unauthorized force.” Officers must also immediately report to their supervisor if they see another officer engage in unlawful force. Police must be protected from retaliation in making such reports, and police who are found to use excessive or unauthorized force must be disciplined.

FOURTH: Illinois needs a robust, statewide system for recording and reporting information about police uses of force, including with respect to SWAT/tactical team deployments.

This system will allow us to assess the success of our efforts over time. It will also allow law enforcement agencies to better assess the actions of officers who repeatedly abuse force.

In conclusion, we cannot quell the anger and frustration of communities toward police without addressing their cause, and we cannot restore community trust in policing unless we earn it. The measures we are proposing today are reasonable, common-sense reforms that will not only benefit the public and save countless Black lives, but also help police across the state do their job more safely and effectively.

Restricting force provides police with needed clarity in their interactions with the public. Requiring police to stop unauthorized uses of force and to report these incidents will change the expectations of policing and departments. And requiring use of force data collection and record

keeping will help keep all of us accountable to the public.

We look forward to working with you, the communities demanding reform, and the law enforcement leaders sworn to protect all of us to make the changes we need.