Today, the Illinois Senate Committee on Public Health held a hearing to assess the Chicago Police Department’s standards and practices for determining gang affiliation, known as its unofficial “gang database.” This so-called database in Chicago has prompted public concern regarding the potential for significantly adverse impacts of this archive, as well as the lack of transparency from CPD on how it tracks and labels those designated as “gang-affiliated.”

The below testimony can be attributed to Rachel Murphy, Staff Attorney, Police Practices Project, ACLU of Illinois:

“My name is Rachel Murphy and I am a staff attorney with the ACLU of Illinois, where I work on issues relating to police practices. Thank you for the opportunity to provide testimony today about our concerns with Chicago’s ‘gang database.’

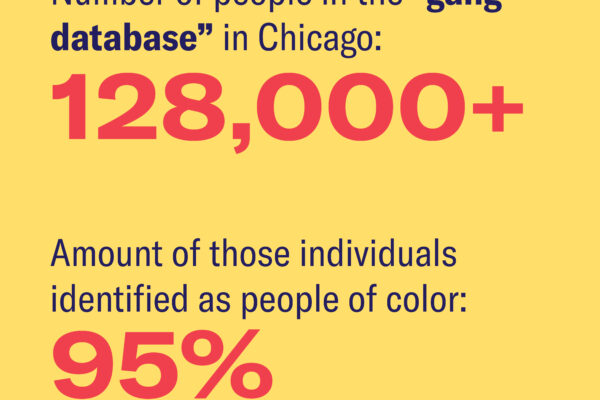

The Chicago Police Department (CPD) collects information on individuals with whom they have had interactions, including whether that person is affiliated with any gangs. As several researchers and reporters have documented, over 128,000 people are identified as gang-affiliated in Chicago, and of these individuals, about 95% are people of color.

These designations can be inaccurate or outdated, but there is no process for an individual to contest the designation or petition for removal. For example, data obtained by ProPublica Illinois showed that individuals were identified as gang-affiliated as far back as 1984, and included many individuals in their seventies, eighties, and even over 100 years old.

There are real consequences to a false designation. CPD uses this information to deny I- bonds, which allow a person to be released on their own recognizance, and CPD factors in gang affiliation to calculate a person’s score on the Strategic Subject List, which ranks an individual’s probability of being a ‘party to violence’ as either a victim or offender. However, this designation is not contained to CPD use. It is also used by immigration officials in considering whether to grant a person’s application for legal status and by prosecutors in considering whether to enhance charges.

The City of Chicago and CPD officials have acknowledged that the database is flawed. In December, the City settled a lawsuit in which it admitted that the plaintiff’s gang designation— which led to a raid on his home and months spent in ICE detention—was false. Earlier this month, Superintendent Eddie Johnson stated that people have been ‘misidentified.’

Yet, despite these admissions, the CPD continues to rely on and share these designations with other agencies. The Office of the Inspector General is currently examining CPD’s use of the gang database and the consequences of being identified as gang-affiliated.

This is a good first step for Chicago, but it is important that cities and law enforcement agencies provide the public with more transparency in order for policy solutions to be proposed. Such transparency would include, for example, proactively releasing the number of individuals who have been designated gang members, their demographic information, how long ago the designation was made, how that data is shared, and how that data is assessed for accuracy.”

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.