By Catherine Louis, Photo Historian & ACLU Volunteer

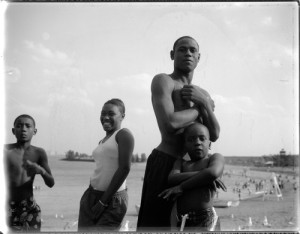

Children embody a moral concern. They’re burdened with society’s hope and conversely, its failure. Photos taken of American children in inhumane situations document the fact that our implicit promise to our children of a better tomorrow has not been kept. They call on us to honor that promise.

Lewis W. Hine was among the first to use photography of children as a call for social reform. From 1906 to 1918, Hine photographed children working on farms, in coal mines and in factories. (1) He took thousands of photos in urban and rural areas, from Maine to Florida, Indiana, Colorado, Oklahoma and Texas. He recorded children toiling on tobacco farms, sugar beet and cotton fields, in canneries, carrying bushels of berries. There are barefoot children handling looms in textile mills; and suited newsies with smoke from their cigarettes swirling about childhood innocence. (2) Field to factory, children are bearing America’s economy on their shoulders. Several children have physical deformities caused by their labors. His children represent many races and both genders; egalitarianism exists on this rung of labor. Hine campaigned for child labor reform.

Mary Ellen Mark’s 1983 photo series of Seattle’s street children had similar aims. (3) She photographed runaway girls and boys in an urban setting of desolate streets and dilapidated buildings, appropriating graffiti’s semiotics and irony. We see young Americans society abandons in the battle weary, baby faced children brandishing guns, smoking joints and slim cigarettes while holding their stuffed toys. Mark intended to give her subjects a voice.(4) Central to Hine’s and Mark’s social and aesthetic imagery are the human figure, place and time. Each photo tells a story. Careful documentation of individual photos–titles, names, dates, locations and brief descriptions, strengthens the impact.

Now at the beginning of a new century children are threatened by gun violence and incarceration. Two exhibits presented at David Weinberg Photography: Carlos Javier Ortiz, We All We Got, (5) and Try Youth As Youth, featuring the work of Richard Ross, Tirtza Even, Steve Davis, and Steve Liss (6) offer evidence that children continue to bear the weight of America’s failure to maintain a fair and just society.

Now at the beginning of a new century children are threatened by gun violence and incarceration. Two exhibits presented at David Weinberg Photography: Carlos Javier Ortiz, We All We Got, (5) and Try Youth As Youth, featuring the work of Richard Ross, Tirtza Even, Steve Davis, and Steve Liss (6) offer evidence that children continue to bear the weight of America’s failure to maintain a fair and just society.

Ortiz’s photographs of grieving families and friends tell us about the debilitating effect of gun violence on American communities. An empty bedroom with favorite clothing laid out across a neatly made twin bed tells us a child’s story has ended. Personal items found in a pocket–bubble gum wrappers and a wadded dollar bill are arranged in a glass viewing case. We step into a smaller light–filled video gallery. The slow rotation of names of each of the fallen passing in procession offers poignant memorials parallel to the war dead.

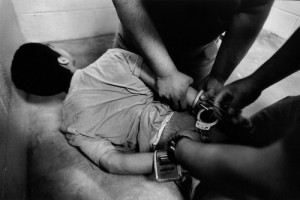

The gallery’s February exhibit displays the work of four artists who document detained and incarcerated children. Try Youth As Youth is a thoughtful, content–oriented visual and audio presentation. Liss’ No Place for Children shows children in a detention center. A small bewildered child wears oversized adult pants, his legs all but disappearing in yards of fabric. A kneeling guard with an instant camera casually positions a child’s cherubic face for a snapshot. We pause at the photo of a grimacing youth, his arms and legs shackled together. By what absurdity does a child enter the adult prison system to be subject to its cruelty?

The gallery’s February exhibit displays the work of four artists who document detained and incarcerated children. Try Youth As Youth is a thoughtful, content–oriented visual and audio presentation. Liss’ No Place for Children shows children in a detention center. A small bewildered child wears oversized adult pants, his legs all but disappearing in yards of fabric. A kneeling guard with an instant camera casually positions a child’s cherubic face for a snapshot. We pause at the photo of a grimacing youth, his arms and legs shackled together. By what absurdity does a child enter the adult prison system to be subject to its cruelty?

Ross’ two series Girls, and Boys of the J Unit includes interviews with the photos. One young woman sits alone at the end of her cot with her back propped against the wall. Reminiscent of a Baroque painting subject, her shadowed face turns away from us with a slight upward tilt toward the room’s light–filled window. Despair fills her tale; we search vainly for whispers of hope. Across the gallery the face of another young woman obscured by hair swept across her eyes is framed in a small square cell door window. Basic personal hygiene products in a baggie outside the cell door reinforce this isolation. We read of tragedy and betrayal in her story.

In another photo a boy alone in a cell stretches out on a cot with his legs propped up in an emotionally void stage–like setting. His loose pants fall gently in folds down his legs. He’s an object like the fixtures, patterns of worn floor paint, and the barren wall. He appears as lifeless as the discarded blanket on the floor. Other photos show restraining rooms with their gruesome paraphernalia of straps and buckles.

Even’s Natural Life incorporates video and sculpture. Cast concrete pillows and bedrolls replicate those issued to incoming detainees. Like the boy in Ross’ photo, the pillows and blankets are transformed. No longer slim comforts for the incarcerated but hardened and resistant. What is more tangible, the irony, as in Mark’s work, or metaphor? The three dimensional aspect draws us in, we’re tempted but hesitate to touch the blanket’s comforting texture, to feel a pillow’s softness that no longer exists. This rich tactile element continues in Even’s video interview of one young prisoner. The camera zooms in on his profile closing in on his temple, so close we distinguish the thickness of his eyelashes and curve of his eyebrow hairs. We actively take part in this surreal aspect; intently watching each blink while reading his story scrolling in the captions at the bottom of the screen. We leave the projection space with reluctance because his story’s not over.

Even’s Natural Life incorporates video and sculpture. Cast concrete pillows and bedrolls replicate those issued to incoming detainees. Like the boy in Ross’ photo, the pillows and blankets are transformed. No longer slim comforts for the incarcerated but hardened and resistant. What is more tangible, the irony, as in Mark’s work, or metaphor? The three dimensional aspect draws us in, we’re tempted but hesitate to touch the blanket’s comforting texture, to feel a pillow’s softness that no longer exists. This rich tactile element continues in Even’s video interview of one young prisoner. The camera zooms in on his profile closing in on his temple, so close we distinguish the thickness of his eyelashes and curve of his eyebrow hairs. We actively take part in this surreal aspect; intently watching each blink while reading his story scrolling in the captions at the bottom of the screen. We leave the projection space with reluctance because his story’s not over.

Davis’ Captured Youth exhibits prisoners’ portraits. Youthful faces look directly at the viewer, returning gaze and thought. A hat, hairstyle, or a hand to the chin gives individual identity. Subtle light exposes a large fading bruise under one young man’s right eye. This nuance leaves questions unanswered. Some are depicted in profile, or with backs turned revealing tattooed shoulders; recalling Mark’s graffiti. One young woman with hands tipped by brightly painted nails shields her face with a white plaster mask that implies anonymity, deconstructing the idea of portraiture. Her cropped figure brings her forward into the viewer’s space. She controls the space and the way we look at her. We get the visually compelling pun.

Davis’ Captured Youth exhibits prisoners’ portraits. Youthful faces look directly at the viewer, returning gaze and thought. A hat, hairstyle, or a hand to the chin gives individual identity. Subtle light exposes a large fading bruise under one young man’s right eye. This nuance leaves questions unanswered. Some are depicted in profile, or with backs turned revealing tattooed shoulders; recalling Mark’s graffiti. One young woman with hands tipped by brightly painted nails shields her face with a white plaster mask that implies anonymity, deconstructing the idea of portraiture. Her cropped figure brings her forward into the viewer’s space. She controls the space and the way we look at her. We get the visually compelling pun.

Liss’ No Place for Children features a black and white photo of boys doing laps in the prison yard. Their shadows on the softly lit concrete brick wall behind them repeat their dark profiles. Their white socks and athletic shoes create the illusion of figures floating in space and suspended in time. Yet the contrasting light and shadow in the clouds and steel grating above them set the lines and shapes in motion. All forms appear choreographed, in sync. Aesthetic beauty draws us in to children’s sadness. Sumptuous imagery counter to troubling subject matter. The paradox draws us in. We look to understand what the children tell us.

Photography’s equipment, technology, publication, distribution and technical language has changed since Hine’s and Mark’s efforts but their call to use photos to document the plight of children remains steadfast. Photographs continue to influence, educate, profoundly disturb and challenge us.

Photography’s equipment, technology, publication, distribution and technical language has changed since Hine’s and Mark’s efforts but their call to use photos to document the plight of children remains steadfast. Photographs continue to influence, educate, profoundly disturb and challenge us.

Learn more about the author Catherine Louis, and view her art on her website, colourisms.com

1) Lewis W. Hine and National Child Labor Committee (NCLC). Photos 1906-1918. Child Labor Legislation 1910s. 2) Lewis W. Hine Collection. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division. Catalog of over five thousand photos of child laborers and campaign materials available online. 3) Mary Ellen Mark. Streetwise, 1983. Series of photos of runaway children, Seattle, WA. Univ of PA Press. June 1988. 4) Mary Ellen Mark. Lillie, Seattle, Streetwise, 1983; and “Rat” and Mike with A Gun; Laura on Pike Street, 1983, Seattle, Washington. 5) Carlos Javier Ortiz, We All We Got. David Weinberg Photography: October 10, 2014 - January 10, 2015. In partnership with ACLU of Illinois. 6) Try Youth As Youth, February 12 - May 8, 2015. Artists: Richard Ross, Girls, and Boys of the J Unit; Tirtza Even, Natural Life, sculpture collaboration with Ivan Martinez; Steve Davis, Captured Youth; Steve Liss, No Place For Children. David Weinberg Photography in affiliation with ACLU of Illinois.